COVID19 and the Great Plague of London

The many ways the response to COVID19 resembles the response to the Great Plague of London in 1665.

From a tweet thread originally posted on April 22, 2020. Some edits have been made for format. Links lead to articles showing modern versions of what went on in history.

Ok, @latxcvi encouraged me so gather 'round for a history lesson on The Great Plague of London and how it relates to #COVID19 in a post I like to call Everything Old Is New Again

The Great Plague of London took place in 1665, one year before The Great Fire of London and entirely in a block of time we might call Living In London May Not Be All It's Cracked Up To Be Now That We Think About It.

The plague in question was mainly bubonic plague but pneumonic and septicemic were part of the mix, because why should any form of plague feel left out.

Bubonic is Ye Olde Black Death, the nasty one with the giant pustules and so on. Speticemic infects the blood, pneumonic infects the lungs. One could possibly say pneumonic is therefore "basically the flu" if one was, as for example, an idiot.

Bubonic is also THE plague. The Black Death. The one which killed a third of Europe back in the mid 1300s. We're going to focus on 1665 London for the most part but there are two key things about reaction to The Black Death which provide interesting comparisons to modern times.

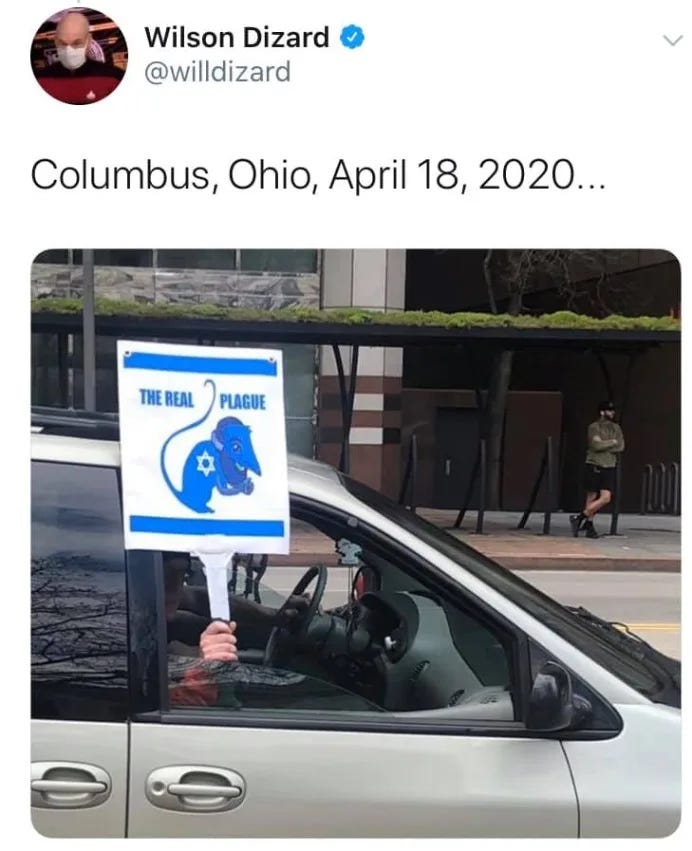

1) When The Black Death started to spread, scapegoats were sought for why that happened. Said scapegoats included immigrants and Jewish people. Because whenever there is a problem, be it plague or a lack of ice cream, the people blamed are ALWAYS immigrants and Jewish people.

and 2) After the Black Death the impact on the population in terms of Those Who Need Work Done (aka royals) and Those Who Actually Did The Fucking Work For Little To No Money (aka everyone else) was such that the entire system of feudalism got torn down.

I'm sure there's NO comparison we can make between #2 and modern times. Ahem.

Anyway, back to London 1665. An important context to know is that while we're fast forwarding about 300 years from The Black Death, plague was actually common during these times. Every 20 years or so there'd be an outbreak.

In point of fact, earlier that century there'd already been a round of plague so bad that for a time it was considered The Great Plague of London. Making a plague version of when Time Travelers go back to 1918 and get the reply of "What do you mean 'World War ONE'?"

So people knew about plague and what it could do. There was no "Only 1530s kids remember buboes!" type thing going on here. Knowledge-wise, nobody had to reinvent the wheel. Which as you'll see is a mixed blessing. Also we're still using the same damn wheel.

Because people understood plague, they were already on the page of plague being Very Very Bad. Thus you want to know if/when people may have died from it because plague is never the kind of thing that stops at killing one person.

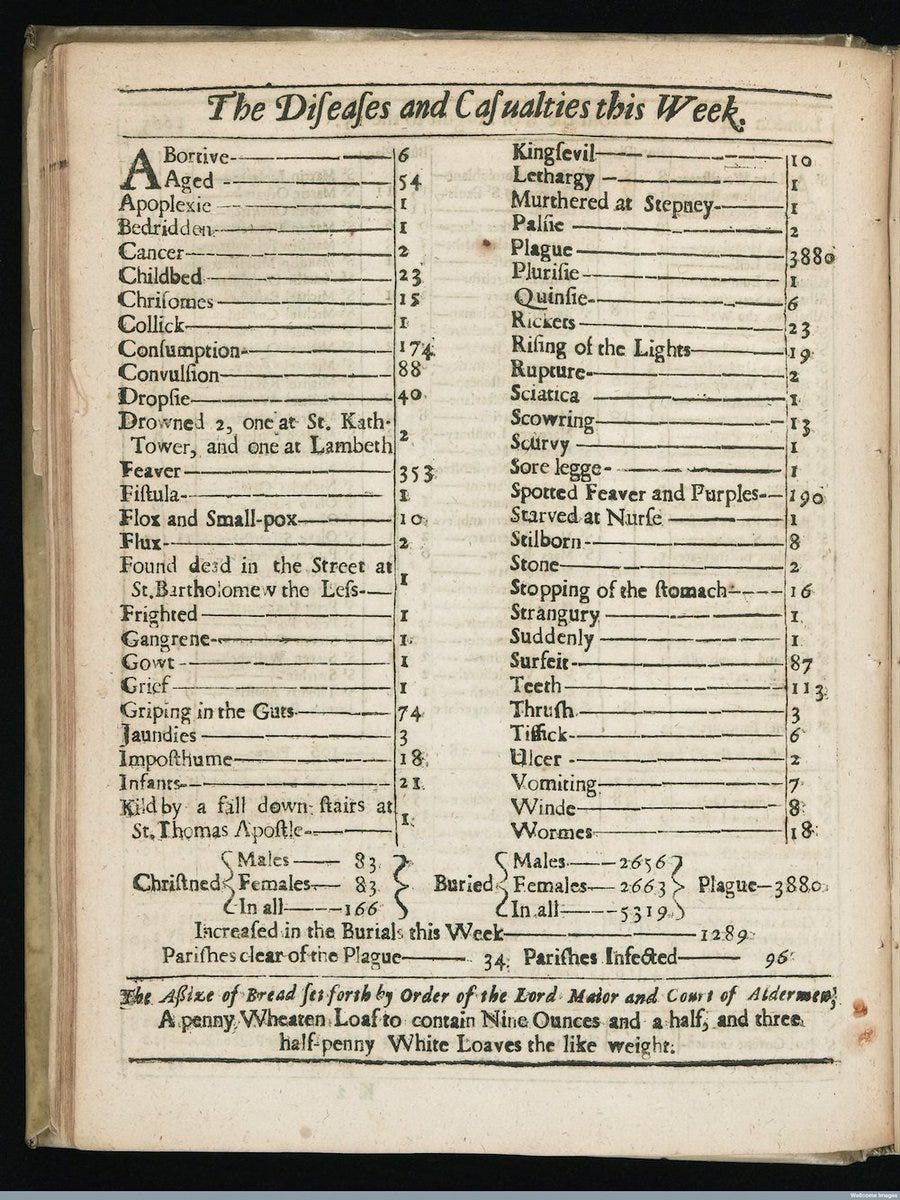

Because Twitter didn't yet exist to give people regular reasons to be depressed, they instead had Bills of Mortality. These were weekly lists of how many deaths there were locally, tallied by cause of death. Plague was important enough to get its own line item.

Now the thing is, plague is not actually a great thing to have in your home town. Which, as I say, people knew. It's not great for leaders to admit plague snuck in. It's not great for families to admit a relative got it. So there was a lot of pressure to deny plague deaths. But Bills of Mortality still needed to be updated. Which meant you might see things like:

- Plague: 0

- Other Illnesses Which Are Totally Not Plague We Swear: 1,000 (up from 5 last week)

Eventually plague became so common you couldn't deny it and the numbers would be put on the bill. But even so there was still pressure to deny, and thus a real count of the death toll required math and logic.

If plague numbers are low but deaths due to fever, coughs, etc are exponentially growing, odds are good it ain't just fever and coughs, yanno? Though this is hard for some to believe.

Likewise there's the issue of how do you know it's a plague death? How do you test for plague in a world without testing? This too had issues. 1) the Bills of Mortality were kept by the church. Thus non-members like Jewish people and Quakers weren't included in any death counts.

2) The way you knew if somebody died of plague was it was determined by a Searcher, which was their version of a Coroner. The Searcher's job was to go to where the dead were, take a look, and decide if it had been plague or something else.

As you might imagine, this was not exactly high on the list of people’s dream careers. Thus it tended to fall to those who couldn't get other work, typically older women in poverty. Literally their only qualification was that they would do the job.

There are those who say Searchers were corrupt, and would take bribes to lie about what they found. I'm not saying these accusations are seeped in misogyny because, well, I shouldn't HAVE to since we've all met the world before.

Consider the Searchers were sent off to live away from other people, purposefully went into homes where there was illness, had no medical training whatsoever, and had as much incentive to tell the truth (or lie) about the presence of plague as anybody else in town. So yeah. There were some issues with accuracy in the numbers due to issues with reporting. Go fig.

Eventually it became clear plague was coming back. Some officials who had seen plague before tried to protect people by shutting down pubs and other places where people gathered. This wasn't great for pub owners, and some people felt that the shutdowns were too soon.

In theory, people were supposed to stay put in London to help contain the spread of the disease. Not a full quarantine (more on that in a bit) but still. You weren't supposed to leave London without special paperwork and permission.

Those who had money, OTOH, fucked RIGHT off out of London. They stayed with friends or in country estates. Others tried to flee as well. This put a strain on the smaller country towns which couldn't handle the influx. Some poorer refugees were sent back.

Among those who left were King Charles II (who went to Hampton Court so I can't blame him, let's be honest), many government officials, doctors (who tended to the rich), and clergy.

The church did more in those days than the government, both for charity and for things like helping out when people were dealing with the wrath of God in plague form. So them being self-serving and defying stay at home orders was considered a huge betrayal.

As for politicians, well it depended. First up you have what we would consider local politicians, such as the Lord Mayor of London. He stayed put and issued orders to stop the spread of plague.

Among the orders were things like hiring the searchers, having doctors around, doing NOTHING WHATSOEVER TO DOGS AND CATS BECAUSE THIS IS MY THREAD AND I SAY SO, DAMN IT, and rules about quarantine.

Quarantine was one of the reasons families were reluctant to report a relative had plague. The rule was that if even one family member had it, everyone in the house had to be put into quarantine with them.

Of course back then quarantine didn't involve 14 days of Netflix and chill like today. Instead, you were locked in your house - literally with a padlock - with the sick person for 40 days. (The word "quarantine" comes from 40). Red crosses were painted on the doors to indicate the house had been hit by plague.

If you were lucky, a nurse might come by to check on you every so often and you might get some food from the parish. Granted this wasn't @WCKitchen level food and the nurses were as qualified as the searchers were, but OTOH consider that right now here in the States we expect people to be in quarantine without any food or additional medical assistance and 1665 was kind of ahead of the game.

As you might imagine, healthy people locked in with sick people didn't stay healthy for long. This was one of the ways that the Mayor's Orders actually didn't help contain the spread.

Another was lack of ability to follow through on things, such as the bit about doctors. Still another was that the plague was already IN London by the time the orders were issued. Maybe if people hadn't been in denial months earlier the measures could've stopped the spread but, well.

As for even higher up levels of government, you'll be happy to know the House of Lords, which moved itself up to Oxford (aka Not London) was on the case. In the summer of that year they finally got around to talking about the whole plague thing and came up with two proposals.

1) That no plague hospital be built near "persons of note and quality" and

2) That no member of the Lords have to be shut up in their house.

Plague hospitals were to help with the issue of quarantining healthy people with sick. The idea was to build special hospitals solely for the care of those with plague, thus containing the illness. Some were built, but in the end they were mostly unused.

Nurses worked the hospitals and quarantined houses. Much like the searchers, nurses during the Great Plague were considered dishonorable and likely to be thieves. Even though, like the searchers, they did a dangerous job no one wanted.

The death count climbed. In terms of records, it went from noting specific payments for burials by name, to general labels like "the boy" to bigger tallies. So many were dying every day it became hard to keep track of.

Likewise there became a lack of room for the bodies. Single graves became quickly consecrated plots of land became mass graves of bodies piled on top of one another with no records of who was in there.

Even the ability to honor the dead went to the side. At the start proper funerals were held. By the end it was barely possible to make sure the ground they were placed in was holy. At first it was a rule to ring a bell for those dead of plague to honor them and inform people of the danger. Eventually they stopped the practice because the death count kept the bells constantly ringing.

Winter eventually came. The spread slowed, and there were those who believed that it might be due to the change in weather.

Because of the slowed spread, people who had left London trickled back in, assuming it would be safe. Turns out the plague didn't care, and there were infections again.

It's felt that in the end the Great Fire of London is part of what helped end the plague. Which... I'm really hoping to not come back to this thread and update it with a link that ties that bad boy to something modern. Yeesh. Some other details worth noting:

Once houses were cleared of plague they were marked with a white X

Anybody who says Ring Around the Rosie is about the black death is wrong.

Though they didn't know about germs, they did have the concept that illness could be spread by breathing it in. They thought it was due to miasma, or bad smells. But, considering the knowledge of the time, this wasn't too weird a conclusion.

Fighting off the bad smells was thus considered a way to protect from plague. They carried around pomanders, herbs, and it was even strongly encouraged that people use tobacco. Fighting off the plague with smells is why our pal the plague doctor had the beak. There were herbs tucked inside.

Other ways people protected themselves was by keeping their distance when conducting business, and using vinegar to clean coins and correspondence before touching them.

In the end about 69,000 people OFFICIALLY died of plague in 1665. Given the earlier mentioned issues, it's thought that the number is actually closer to 100,000, or a quarter of London's population at the time. Again I'm really hoping that I don't come back and update this thread with something that ties that number to modern times. [ETA: Sigh.]

But! Point being that you can see that there's a cycle to these things, those who don't learn history are doomed to yadda yadda. Or, as I said at the start of this thread: